Sgt. Jerry Norman Duffey

Fort Pierce Mother Remembers Son Who Fought, Died in Vietnam.

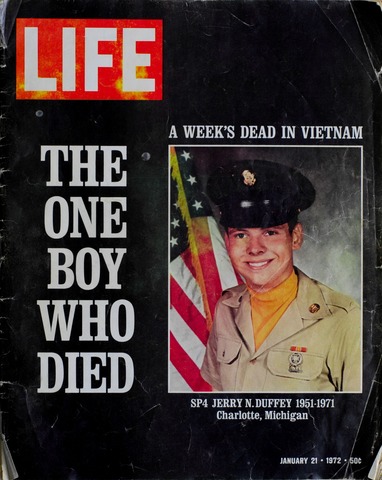

A month after Sgt. Jerry Norman Duffey was killed in Binh Dinh, South Vietnam, Life magazine dedicated its cover and a feature story to the Army trooper.On the grand scale, the 20-year-old from Michigan wasn't more or less special than those with whom he served. His death wasn't on account of any over-the-top heroic action.

He was killed when Hill 131 — the hill was named for its height in meters — was mortared and attacked by Vietcong sappers with explosives. Duffey's position was undermanned and no longer lit well enough to see the enemy, according to the magazine.

His mother, Fort Pierce resident Joyce Cope, hangs tight to her memories of her eldest son, whose life, more than his death, was recounted in the pages of Life on Jan. 21, 1972.

"It's something that happened in my life, but the hurt never goes away," said the Gold Star Mother who has lived on the Treasure Coast for 30 years. Gold Star Mothers is an organization of mothers who have lost a son or daughter in service of the United States.

Now 73, she wanted to share the story.

Duff, as his friends called him, died for his country 19 days before the hill was to be turned over to the South Vietnamese. At the time, he was one of 45,000 Americans killed in Vietnam. President Nixon commented on Duffey's death during a televised interview as an example of the on-going de-escalation of troops.

Duffey was highlighted because he was the only death announced in a weekly reporting period. At the time it was the lowest number of recorded deaths for a reporting period since a week in February 1965, when no one was killed.

"It was kind of a political thing. He wasn't really special, but he was special to me," said Cope. "They asked if they could write the story. We didn't get any money, but it was an honor to have it written. And I thought they did a really nice job on the story."

To Joyce Cope, he was more than just the oldest of her five children, who have given her seven grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. "He was a really nice boy and really well liked in the community."

Jerry grew up on a farmhouse in a town called Sunfield, Mich., about 30 miles from Lansing. At 10 he began raising chickens and selling them. He sold enough that at age 11 he bought himself a horse he called Comanche. He later turned his interests to auto mechanics. But the war was always in the background. Buddies were being drafted or enlisted, so at 19 he decided to volunteer.

His first overseas assignment was Germany, to the ease of his father Stub Duffey, who questioned the war in the magazine. Three months after Jerry was born, Stub had been drafted and sent to Korea, returning when Jerry was 21 months.

However, it wasn't too long before Jerry Duffey was off to Vietnam. He even agreed to extend his tour by six months so he could get home leave for Christmas in 1971. But he never made it.

On Dec. 12, 1971, he was working the "graveyard watch" when Vietcong slipped through jagged wire and blew up several buildings, leaving 17 GIs injured and Duffey dead.

It would be more than a week before his mother learned of his death.

"It was a very tough Christmas, it was really hard on the other children," Cope said. "But we had many friends and we thanked the Lord for that."

A month after Sgt. Jerry Norman Duffey was killed in Binh Dinh, South Vietnam, Life magazine dedicated its cover and a feature story to the Army trooper.On the grand scale, the 20-year-old from Michigan wasn't more or less special than those with whom he served. His death wasn't on account of any over-the-top heroic action.

He was killed when Hill 131 — the hill was named for its height in meters — was mortared and attacked by Vietcong sappers with explosives. Duffey's position was undermanned and no longer lit well enough to see the enemy, according to the magazine.

His mother, Fort Pierce resident Joyce Cope, hangs tight to her memories of her eldest son, whose life, more than his death, was recounted in the pages of Life on Jan. 21, 1972.

"It's something that happened in my life, but the hurt never goes away," said the Gold Star Mother who has lived on the Treasure Coast for 30 years. Gold Star Mothers is an organization of mothers who have lost a son or daughter in service of the United States.

Now 73, she wanted to share the story.

Duff, as his friends called him, died for his country 19 days before the hill was to be turned over to the South Vietnamese. At the time, he was one of 45,000 Americans killed in Vietnam. President Nixon commented on Duffey's death during a televised interview as an example of the on-going de-escalation of troops.

Duffey was highlighted because he was the only death announced in a weekly reporting period. At the time it was the lowest number of recorded deaths for a reporting period since a week in February 1965, when no one was killed.

"It was kind of a political thing. He wasn't really special, but he was special to me," said Cope. "They asked if they could write the story. We didn't get any money, but it was an honor to have it written. And I thought they did a really nice job on the story."

To Joyce Cope, he was more than just the oldest of her five children, who have given her seven grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. "He was a really nice boy and really well liked in the community."

Jerry grew up on a farmhouse in a town called Sunfield, Mich., about 30 miles from Lansing. At 10 he began raising chickens and selling them. He sold enough that at age 11 he bought himself a horse he called Comanche. He later turned his interests to auto mechanics. But the war was always in the background. Buddies were being drafted or enlisted, so at 19 he decided to volunteer.

His first overseas assignment was Germany, to the ease of his father Stub Duffey, who questioned the war in the magazine. Three months after Jerry was born, Stub had been drafted and sent to Korea, returning when Jerry was 21 months.

However, it wasn't too long before Jerry Duffey was off to Vietnam. He even agreed to extend his tour by six months so he could get home leave for Christmas in 1971. But he never made it.

On Dec. 12, 1971, he was working the "graveyard watch" when Vietcong slipped through jagged wire and blew up several buildings, leaving 17 GIs injured and Duffey dead.

It would be more than a week before his mother learned of his death.

"It was a very tough Christmas, it was really hard on the other children," Cope said. "But we had many friends and we thanked the Lord for that."